Python for Game Designers: Simulating a Simple 1v1 Fight

Introduction

In the previous article, I explored why game designers should consider using Python. Now, we’ll dive into a simple example of a game simulation to show how Python can be useful for balancing mechanics. This article demonstrates a straightforward 1v1 fight simulation, highlighting how simulations can help refine gameplay and test balance in a controlled environment.

Game Mechanics Overview

In this example, we’ll simulate a simplified 1v1 fight mechanic — a concept I’ve used in balancing for AILeague Arena. This type of mechanic is common in games where players summon units to defend a tower or attack an enemy. To keep things straightforward, we’ll assume the game is 2D, with units moving along a single axis toward enemy towers. Each unit has an attack range and cooldown; when an enemy enters its range, it will attack. Since damage is processed simultaneously, ties are possible, making this simulation particularly useful for understanding balance and unit interactions. Another example of a similar game mechanic is “Swords & Soldiers” by Ronimo Games.

Getting Started

To follow along with this example, you’ll need access to Jupyter notebooks. You can install Jupyter locally by following the instructions on Jupyter’s official site at https://jupyter.org/install. Alternatively, you can use an online tool like Google Colab (https://colab.research.google.com/), which lets you start coding immediately without any installation.

The code for this article is available on the GitHub repository.

Overview of Units and Attributes

Let’s take a classic set of fantasy units: soldier, knight, archer, goblin, ork, and axe-thrower. This gives us two factions with a mix of melee and ranged units. Each unit is defined by specific parameters essential to combat simulation. We start with health, which tracks the unit’s current state. For attacks, we have attack_damage, determining how much damage each strike deals, and attack_cooldown, which defines the time between attacks, ensuring units don’t attack every frame. Ideally, this cooldown should align with the game’s frame duration for smoother timing. Attack_range is also crucial, as units move toward each other, and even melee units need a defined reach. Finally, we have speed, representing movement in meters per second (or another distance unit), allowing us to simulate their approach and positioning in combat.

Data Structure for Units and Attributes

To manage units and their attributes, we’ll use classes to allow direct access to properties with dot notation. While there are other options, such as named tuples or pandas dataframes, this example focuses on using basic Python structures to keep things accessible. The core attributes for each unit type are stored in a dictionary (UNITS_ATTRIBUTES), making it easy to read and modify initial stats as needed. Global constants are written in uppercase (UNITS_ATTRIBUTES and UNIT_TYPES), while unit names use hyphen style.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

UNITS_ATTRIBUTES = {

'soldier': {'health': 100, 'attack_damage': 10, 'speed': 1.5, 'attack_range': 1, 'attack_cooldown': 0.7},

'knight': {'health': 150, 'attack_damage': 15, 'speed': 1.2, 'attack_range': 1, 'attack_cooldown': 1},

'archer': {'health': 50, 'attack_damage': 20, 'speed': 1, 'attack_range': 10, 'attack_cooldown': 2},

'goblin': {'health': 50, 'attack_damage': 10, 'speed': 1.5, 'attack_range': 1, 'attack_cooldown': 0.5},

'ork': {'health': 100, 'attack_damage': 15, 'speed': 1.2, 'attack_range': 1, 'attack_cooldown': 1},

'axe-thrower': {'health': 50, 'attack_damage': 20, 'speed': 1, 'attack_range': 10, 'attack_cooldown': 2}

}

UNIT_TYPES = list(UNITS_ATTRIBUTES.keys())

UNIT_TYPES is a list of unit names that we’ll use frequently, so it’s initialized once to avoid repeatedly accessing the keys of UNITS_ATTRIBUTES.

To encapsulate attributes, the UnitAttributes class gives us dot access to properties instead of needing to use dictionary keys. Here’s the implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

class UnitAttributes:

def __init__(self, unit_type: str):

self.unit_type = unit_type

self.attack_damage = UNITS_ATTRIBUTES[unit_type]['attack_damage']

self.speed = UNITS_ATTRIBUTES[unit_type]['speed']

self.attack_range = UNITS_ATTRIBUTES[unit_type]['attack_range']

self.attack_cooldown = UNITS_ATTRIBUTES[unit_type]['attack_cooldown']

self.health = UNITS_ATTRIBUTES[unit_type]['health']

The Unit class stores additional data to manage each unit’s state during combat, including:

x– the unit’s position.max_healthandcurrent_health– to track health changes separately (useful if healing is introduced).current_attack_cooldown– to track the remaining time until the unit can attack again.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

class Unit:

def __init__(self, unit_type: str, x=0):

self.type = unit_type

self.attributes = UnitAttributes(unit_type)

self.max_health = self.attributes.health

self.current_health = self.max_health

self.current_attack_cooldown = 0

self.x = x

This structure keeps the code readable and efficient for simulating combat and tracking each unit’s state. In future we move to more complex but more flexible data structures like pandas dataframes and interactive spreadsheets.

Functions for Core Mechanics

Before starting the simulation, we’ll define some constants that help control game balance.

DT— DeltaTime, or the frame duration for our simulation. A value of0.1works well for our needs, though you can adjust it to fine-tune the simulation.FIELD_SIZE— The starting distance between units, set to match or exceed the longest attack range in our example.

1

2

DT = 0.01

FIELD_SIZE = 15

Now, let’s introduce some helper functions. These functions support repeated operations and make the main simulation logic easier to follow.

To simplify unit creation, create_unit acts as a wrapper for initializing units. Units starting on the left have x = 0, while those on the right start at FIELD_SIZE.

1

2

def create_unit(unit_type: str, x=0) -> Unit:

return Unit(unit_type, x)

Distance calculations are essential in any game, even non-combat ones (Levenshtein distance for word games), so we define distance_between to measure the separation between two units.

1

2

def distance_between(unit1: Unit, unit2: Unit):

return abs(unit1.x - unit2.x)

The function enemy_in_range checks if an enemy is within a unit’s attack range, which is crucial for deciding when ready to reduce the health of an opponent.

1

2

def enemy_in_range(unit: Unit, enemy: Unit):

return distance_between(unit, enemy) <= unit.attributes.attack_range

Timing for attacks is controlled by unit_can_attack, which verifies if a unit’s attack cooldown has reset, allowing it to attack again.

1

2

def unit_can_attack(unit: Unit):

return unit.current_attack_cooldown <= 0

Handling attacks is done by process_attack, a function that changes the state of its arguments—decreasing the enemy’s health and resetting the attacker’s cooldown. Using state-modifying functions requires caution, as they alter properties of other objects directly.

1

2

3

4

5

6

def process_attack(unit: Unit, enemy: Unit) -> bool:

if not unit_can_attack(unit):

return False

enemy.current_health -= unit.attributes.attack_damage

unit.current_attack_cooldown = unit.attributes.attack_cooldown

return True

Finally, move_unit adjusts the unit’s position as it advances toward an opponent. Its name reflects its purpose, though it’s also a state-modifying function.

1

2

def move_unit(unit: Unit, direction: int):

unit.x += unit.attributes.speed * direction * DT

With these constants and helper functions, we’re ready to move into the simulation logic. They provide a solid foundation, improving readability and reducing repetitive code.

Simulating Combat Mechanics

With our helper functions in place, the core fight simulation becomes straightforward and readable. In designing simulate_fight, I prioritized code clarity over complexity, avoiding nested conditionals or list comprehensions. This function takes two unit types as input, initializing two units—one starting on the left and the other on the right. Since both units act simultaneously, their positions offer no inherent advantage.

The fight begins by setting time to zero, and a while loop runs as long as both units have health remaining. Inside this loop, we check if each unit has an enemy within attack range. If a unit is in range, process_attack is called, where attack cooldowns are enforced, and enemy health is reduced. Notably, we only check health at the beginning of each loop, meaning a “dead” unit can still deliver a final strike if attacked during the same cycle.

When units are out of range, they advance toward each other with move_unit. At the end of each loop cycle, we decrement each unit’s attack_cooldown, ensuring it doesn’t drop below zero, and increment time by DT to track the fight duration.

Once the fight concludes, simulate_fight returns three values: the duration, the remaining health of unit1, and the remaining health of unit2.

A note on the while loop: This approach works well for a simple fight, but if we added mechanics like healing or incorrect speeds, the loop could theoretically run indefinitely. A time-based stopping condition might be a helpful addition for future versions, though it’s beyond this article’s scope.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

def simulate_fight(unit_type1: str, unit_type2: str):

unit1 = create_unit(unit_type1, 0)

unit2 = create_unit(unit_type2, FIELD_SIZE)

time = 0

while unit1.current_health > 0 and unit2.current_health > 0:

if enemy_in_range(unit1, unit2):

process_attack(unit1, unit2)

else:

move_unit(unit1, 1)

if enemy_in_range(unit2, unit1):

process_attack(unit2, unit1)

else:

move_unit(unit2, -1)

time += DT

unit1.current_attack_cooldown = max(0, unit1.current_attack_cooldown - DT)

unit2.current_attack_cooldown = max(0, unit2.current_attack_cooldown - DT)

return time, unit1, unit2

Running the Simulation

With our combat logic in place, we can now run a full tournament to observe outcomes across all unit pairings. By adjusting UNIT_ATTRIBUTES, we can easily re-run the tournament to test balance changes (remember to re-run the cell after any updates to constants to apply them). The loop below initiates a series of 1v1 matches, where each unit type faces off against every other unit type.

1

2

3

4

5

results = []

for unit_type1 in UNIT_TYPES:

for unit_type2 in UNIT_TYPES:

t, u1, u2 = simulate_fight(unit_type1, unit_type2)

results.append((t, u1, u2))

Since there’s no randomness in this simulation, each match has a consistent outcome, so we only need one match per pairing. However, in future iterations, we may introduce randomness to simulate variations in combat, at which point we can analyze average outcomes or use medians to gauge balance across multiple rounds.

Displaying the Results in a Table

To analyze our simulation outcomes, we need a clear way to view the results. This is where Python notebooks and data visualization tools can shine, making analysis far more flexible than traditional spreadsheets. However, for simplicity in this article, we’ll use plain ASCII tables and text to display the outcomes. To help with formatting options for our printed results, I used GitHub Copilot to streamline the code and mix formatting styles easily.

The print_results function provides a quick summary of each fight, showing which unit won, how long the fight lasted, and the remaining health of the winner. This function makes it easy to follow the outcome of each individual match.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

def print_results(results):

for time, unit1, unit2 in results:

print('-' * 50)

time = round(time, 1)

print(f'Fight between {unit1.type} and {unit2.type} lasted {time} seconds')

if unit1.current_health > 0:

print(f'Winner: {unit1.type} with remaining health {unit1.current_health}')

elif unit2.current_health > 0:

print(f'Winner: {unit2.type} with remaining health {unit2.current_health}')

else:

print('Draw, both units died')

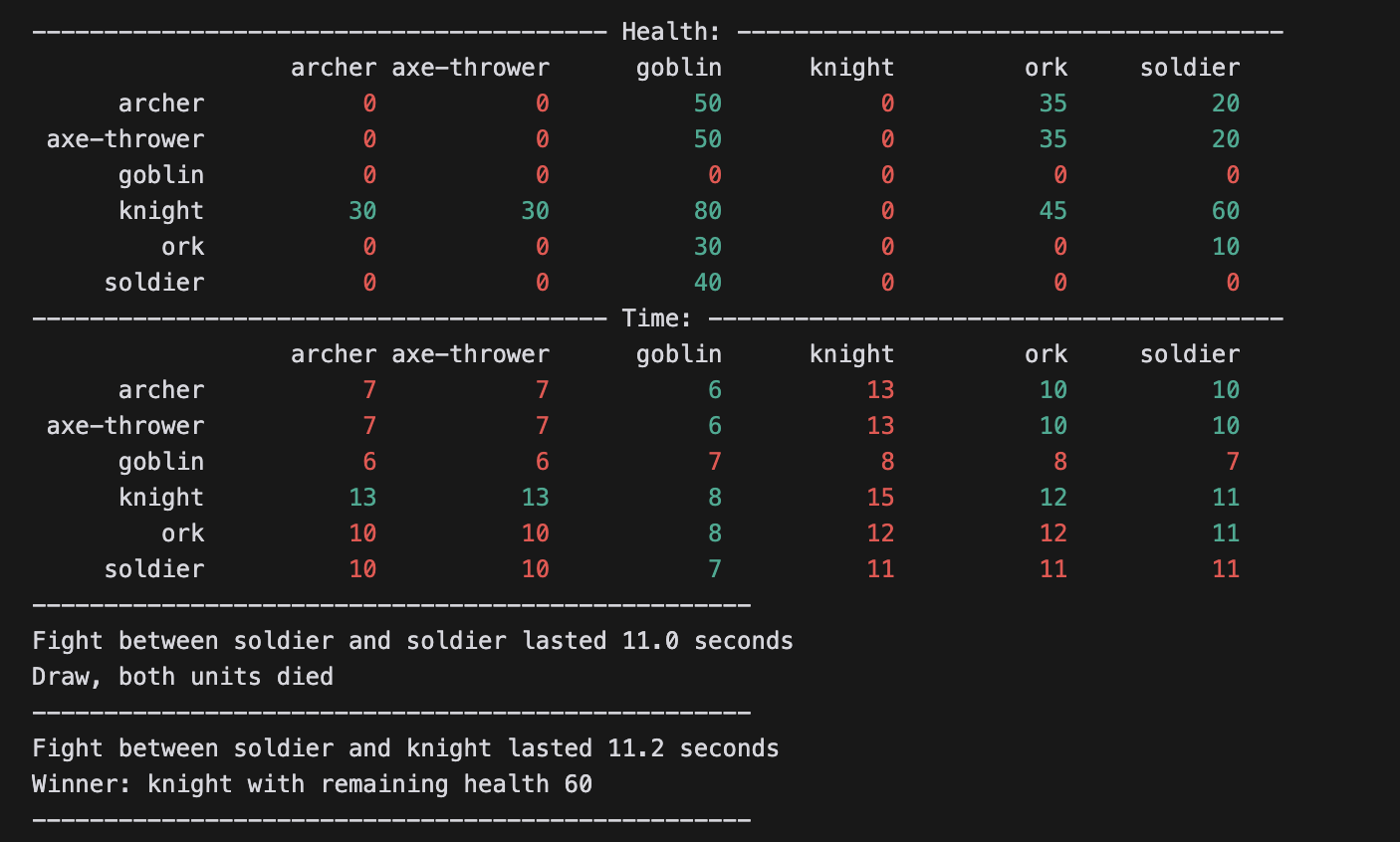

The print_results_table function organizes results into an ASCII table, showing the remaining health or fight duration for each unit pairing. This structure makes it easy to spot which units tend to win or lose against others. Rows and columns represent unit types, and cell values display the selected metric (either remaining health or time). Color coding is applied, with green indicating units that survive and red for those defeated.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

def print_results_table(results, cell_type="health"):

# first we need to find all unique unit types

INTENT = 12

unit_types = set()

for _, unit1, unit2 in results:

unit_types.add(unit1.type)

unit_types.add(unit2.type)

unit_types = sorted(list(unit_types))

# print header

print(' ' * INTENT, end='')

for unit_type in unit_types:

print(f'{unit_type:>{INTENT}}', end='')

print()

# print rows

for unit_type1 in unit_types:

print(f'{unit_type1:>{INTENT}}', end='')

for unit_type2 in unit_types:

# find result for this pair of unit types

for time, u1, u2 in results:

if u1.type == unit_type1 and u2.type == unit_type2:

break

else:

raise Exception(f'No result for {unit_type1} vs {unit_type2}')

hp = max(u1.current_health, 0)

if cell_type == "health":

cell_data = hp

elif cell_type == "time":

cell_data = time

else:

raise Exception(f'Unknown cell type: {cell_type}')

if hp == 0:

print(f'\x1b[31m{cell_data:>{INTENT}.0f}\x1b[0m', end='')

else:

print(f'\x1b[32m{cell_data:>{INTENT}.0f}\x1b[0m', end='')

print()

To display both health and fight duration results, use these commands:

1

2

3

4

5

print("-" * 40 + " Health: " + "-" * 38)

print_results_table(results, cell_type="health")

print("-" * 40 + " Time: " + "-" * 40)

print_results_table(results, cell_type="time")

print_results(results)

These functions let us see at a glance which units prevail and the typical duration of each fight, providing insights into balance and performance for each unit type. Here is how it looks in the notebook:

Analyzing and Interpreting Results

With these results in hand, we can start adjusting unit attributes, game logic, field size, and more to fine-tune the balance. Even in its simple form, this simulation provides a clearer picture than basic formulas in a spreadsheet. For example, the current setup shows that knights are overpowered while goblins struggle as basic cannon fodder. Of course, we’re not yet factoring in costs, crowd dynamics, or abilities that would affect real gameplay balance—topics we’ll explore in future articles. This method is a practical starting point for understanding balance in turn-based combat, offering game designers an accessible way to test and iterate on mechanics.

Conclusion

This example illustrates how Python can be a powerful tool for simulating game mechanics, even in a straightforward combat model. By creating a simple 1v1 fight simulation, we gain insights into unit balance and interactions, providing a foundation for more nuanced adjustments. As we continue in this series, we’ll explore more complex mechanics, adding layers such as costs, abilities, and group dynamics to refine and deepen our simulations. Python’s flexibility and readability make it ideal for this iterative approach, allowing game designers to test ideas efficiently and make data-driven adjustments.